Instructions for Using the Guide and the Information Booklet

Familiarize yourself with the questions, statements, and birth control methods matrix in the Conversation Starters and Birth Control Methods Matrix ahead of talking with a young person. For additional guidance, read Activate’s “Seven Tips for Youth-Supporting Professionals for Talking with Youth about Sexual and Reproductive Health.”

- Review the Background section which summarizes the research informing this Guide.

- Reflect on the five conversation-starters questions below before starting a conversation about birth control with a young person.

- Record the young person’s responses or have the young person record their responses to the five conversation-starter questions.

- Read each of the ten statements described in “Using the Birth Control Matrix” below to the young person, or have them read the statements aloud and note which they agree with. Young people may agree with more than one statement.

- Highlight the columns in the Birth Control Methods Matrix below that correspond to the statements with which the young person agrees. You may need to highlight more than one column.

- Look for the symbols that appear in all or most of the highlighted columns. These symbols represent the birth methods that best align with the young person’s preferences, needs, and priorities. Their preferences, needs, and priorities may align with more than one method of birth control.

- Provide the young person with the page(s) in the Information Booklet that correspond to the birth control methods that best align with their preferences, needs, and priorities.

- Refer young people who want additional information about their birth control options to the following online tools:

– Bedsider has an online tool for exploring birth control options. It is designed for women ages 18 to 29 and operated by Power to Decide: The Campaign to Prevent Unplanned Pregnancy.

– Planned Parenthood has an online tool for exploring birth control options.

You should also feel free to use the Guide and Information Booklet in whatever way is most helpful to you and to the young people with whom you work.

Background

Birth control is a personal choice that involves many considerations

Choosing to use birth control (also known as contraception) and choosing which birth control method to use are extremely personal decisions. No birth control method is right for everyone, and what works best for one person may not work best for another.

To make an informed choice about which birth control method to use—or whether to use any method at all—young people need medically accurate information about the full range of birth control options. Moreover, because they are still building decision-making autonomy regarding their sexual and reproductive health, they may also need support in choosing a birth control method.[1] This may be especially important for young people who are involved with the child welfare or justice systems, experiencing homelessness, or disconnected from school and work.

Research on factors that influence birth control choice has focused on young cisgender women[a]

Research suggests that young, cisgender women in the general population who are choosing a birth control method must consider the attributes of different methods, such as side effects, effectiveness, cost, effort involved, and user control; contextual factors, such as reproductive history, relationship characteristics and previous contraceptive experiences, and attitudes toward pregnancy; and factual and experiential information provided by peers, family members, and health care providers.[2],[3]

Research on factors that influence birth control choice among young people with certain experiences is limited

Comparatively fewer studies have looked at the factors that are important to young people who experience the child welfare and/or justice systems, homelessness, and/or disconnection from work and school when they are choosing what birth control to use. Furthermore, these studies involve small, nonrepresentative samples, so their findings may not generalize to the population of young people who experience the child welfare and/or justice systems, homelessness, and/or disconnection from work and school. Despite their limitations, the studies do point to some of the same factors that influence the contraceptive choices of young, cisgender women in the general population. These include the experiences of family and friends,[4] the responses of their partners,[3],[5] maintenance requirements,[6] side effects,[7],8] insurance coverage,[6] and pregnancy attitudes.[9] Finally, research suggests that these young people want more information about their contraceptive options, including information about side effects and relative effectiveness.[6]

Some populations of young people have been excluded from most research on factors that influence birth control choice

To date, young cisgender men have largely been excluded from research on factors that influence young people’s choice of birth control methods. Some studies examine the role that partners play in decision making about birth control, but none of these studies included young cisgender men as study participants. Two factors probably contribute to the exclusion of young cisgender men from this research. First, the birth control options available to young cisgender men are far more limited than those available to young cisgender women. Second, young cisgender women are often the focus of research because they are most directly affected when a birth control method fails, and a pregnancy occurs. However, excluding young cisgender men from this research reinforces the notion that young men have no role to play in pregnancy prevention and that young cisgender women are solely responsible for using birth control.

Young people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer/questioning (LGBTQ+) or gender non-binary have also been excluded from much of the research on contraceptive choice.[b] Many researchers assume incorrectly that these young people are not at risk for pregnancy, and exclude them from studies as a result.[10],[11] This reinforces the assumption that only heterosexual relationships are normal when it comes to young people’s sexual behaviors and contraceptive needs. There are, however, exceptions: some studies have found that transgender and non-binary young people tend to seek contraception that will both prevent pregnancy and suppress menstruation,[12],[13],[14] and that lesbian or bisexual women tend to prefer short-acting birth control methods.[15],[16]

Given that non-binary or LGBTQ+ young people are overrepresented among young people involved with the child welfare and/or justice systems, experiencing homelessness, and/or disconnected from work and school, [17],[18],[19],[20],[21] it is important for youth-supporting professionals to avoid making assumptions about young people’s needs or preferences based on their gender identity, sexual orientation, or sex assigned at birth. (For guidance on providing LGBTQ+ affirming care, please see Activate’s “Using Trauma-Responsive, LGBTQ+ Affirming Care to Connect Young People to Sexual and Reproductive Health Services.”)

Conversation Starters and Birth Control Methods Matrix

The Conversation Starters and Birth Control Methods Matrix aim to help professionals facilitate a conversation with young people about choosing the birth control methods best for them. This section of the Guide includes questions to start the conversation; statements to help young people identify their birth control preferences, needs, and priorities; and a birth control methods matrix that professionals can use interactively with young people to guide their decision-making about birth control methods and aid in using the Information Booklet.

Before Starting a Conversation with Young People about Choosing Birth Control

We recommend reflecting on the following five questions before starting a conversation about birth control with a young person:

| 1. Is your location one in which the young person will feel safe and you can have a private conversation? |

| 2. Will you feel comfortable having a conversation about choosing a birth control method with this young person? |

| 3. Are you prepared to listen to the young person and avoid being judgmental? |

| 4. Have you built enough rapport with the young person to ask sensitive questions? |

| 5. Do you believe you are the best person to have this conversation with the young person? |

Questions to Start Conversations about Choosing Birth Control

You can use these questions to begin a conversation about choosing birth control. Questions 1 and 2 ask young people to describe their interests in having children in the future and their current birth control choices. Questions 3 to 7 ask young people to think about their ability to access birth control.

Some questions may be particularly relevant for young people involved with the child welfare and/or justice systems, experiencing homelessness, and/or disconnected from work and school. The birth control choices of these young people may also be affected by factors not reflected in these questions. For example, because young people experiencing homelessness may not have health insurance or a health care provider, they may choose a method that is inexpensive and available over the counter.[22] Likewise, the methods that young people in foster care choose may depend on whether they are living in a foster home, a group care setting, or their own apartment.

| 1. Do you see yourself having a child (or another child) in the future? If so, when? |

| 2. What, if any, form of birth control are you currently using? Why did you choose that form of birth control? |

| 3. Do you have someone you can count on to help you access birth control? |

| 4. What barriers might make it difficult for you to access birth control? |

| 5. Do you have a health care provider you feel comfortable going to? |

| 6. Do you have transportation to a health care provider? |

| 7. Do you have health insurance? |

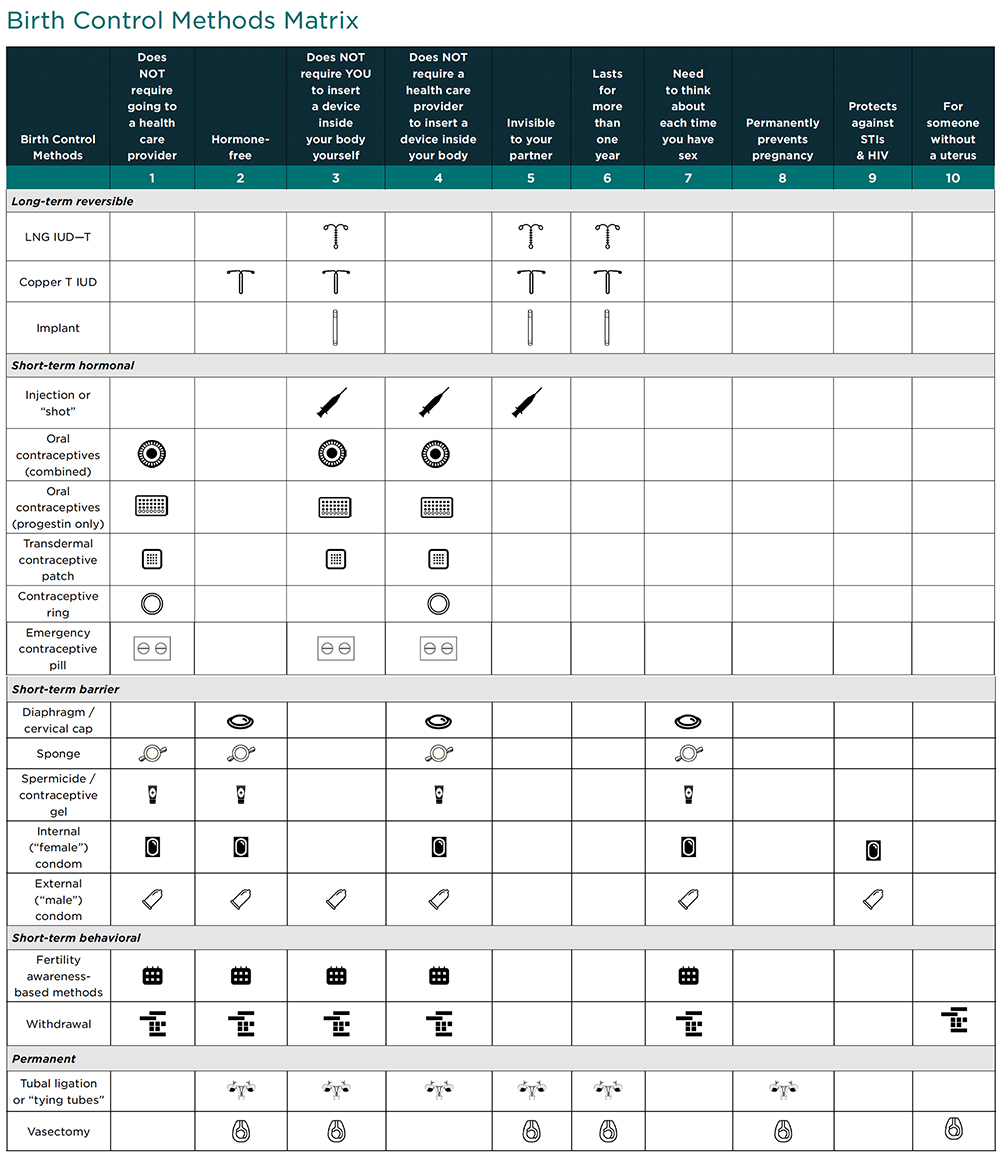

Using the Birth Control Methods Matrix

You can use the 10 statements below to help young people choose a contraceptive method that is right for them. Each statement focuses on a feature of certain contraceptive methods that may or may not be important to a particular young person. Read each statement with the young person or ask them to read the statement and ask whether they agree or disagree. If the young person agrees with the statement, the table indicates which column(s) they should look at in the contraceptive matrix for birth control methods that align with their preferences, needs, and priorities. Young people may agree with more than one statement so they may have to look at more than one column to find the birth control methods with which their preferences, needs, and priorities are best aligned.

| If agree, go to | |

| 1. I prefer a method that I can get without going to a health care provider. | Column 1 |

| 2. I prefer to have a hormone-free method. | Column 2 |

| 3. I would not feel comfortable inserting a birth control device inside my body. | Column 3 |

| 4. I would not feel comfortable having a health care provider insert a birth control device inside my body. | Column 4 |

| 5. I prefer a method that will be invisible to my partner. | Column 5 |

| 6. I prefer a method that will last for more than a year. | Column 6 |

| 7. I prefer a method that I only use or think about when I have sex. | Column 7 |

| 8. I prefer a method that will permanently prevent pregnancy. | Column 8 |

| 9. I prefer a method that also protects against STIs/HIV. | Column 9 |

| 10. I need a method for someone with a penis/without a uterus. | Column 10 |

Note: These statements are designed help young people identify the birth control methods they might want to consider. However, they do not cover the full range of factors that may be important when it comes to choosing a method of birth control. For example, they do not address the side effects or potential benefits of some birth control methods. That information, along with other details about each method, can be found in the Information Booklet. The information in the booklet can also be shared with young people to help them further narrow down their choice of birth control. Depending on the birth control method they choose, young people may need an appointment with a healthcare provider.

The birth control methods in the matrix are divided into five categories:

Use the Matrix as a starting point to identify possible birth control methods with young people. The Information Booklet provides important and more detailed information about each birth control method that young people select. You can print and share the information about each birth control method to help young people to choose the birth control method that is right for them.

Long-term reversible: These are the most effective reversible methods of birth control, last for several years, and can be removed at any time.

Short-term hormonal: These birth control methods use hormones to prevent pregnancy. They are effective but not as effective as long-term reversible methods.

Short-term barrier: These birth control methods prevent pregnancy by blocking sperm from passing through the cervix. They are less effective than long-term reversible or hormonal methods.

Short-term behavioral: These birth control methods require users to engage in specific behaviors to prevent pregnancy. They are less effective than long-term reversible or hormonal methods.

Permanent: These birth control methods permanently prevent pregnancy and are highly effective.

*In some states, these birth control methods can either be prescribed by a pharmacist or dispensed by a pharmacist without a prescription. To see if you live in one of these states, go to https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/pharmacist-prescribed-contraceptives.

Suggested Citation: Griffin, A. M., Schlecht, C., Pliskin, E., & Dworsky, A. (2022). Helping young people choose the birth control method right for them: A guide for youth supporting professionals. Child Trends. https://activatecenter.org/resource/helping-young-people-choose-birth-control-method-right-for-them-guide-youth-supporting-professionals

Attribution: This resource was developed as part of a partnership between Child Trends and Chapin Hall. Authors of this resource from Chapin Hall include Amanda Griffin, Ph.D, Colleen Schlecht, MPP, and Amy Dworsky, Ph.D.

Footnotes

[a] The term cisgender refers to a person whose gender identity corresponds with the gender they were assigned at birth. A cisgender woman is a person who identifies as a woman and was assigned female at birth; a cisgender man is a person who identifies as a man and was assigned male at birth.

[b] People with nonbinary gender identities do not identify exclusively as women or men.

-

References

-

Acknowledgments